Most articles will tell you that saffron is expensive because it’s “labour intensive” or because it comes from a delicate flower. And while that’s true, it’s also a shallow explanation.

This article is different. I’m writing this not just as a food lover or researcher, but as someone who actually belongs to a small group of family farmers. People who plant, nurture, pick, separate, dry and pack saffron by hand. Between three families, we share half a hectare (1.2 acres) of land, and every year we produce about 2 kilograms of saffron. That’s it.

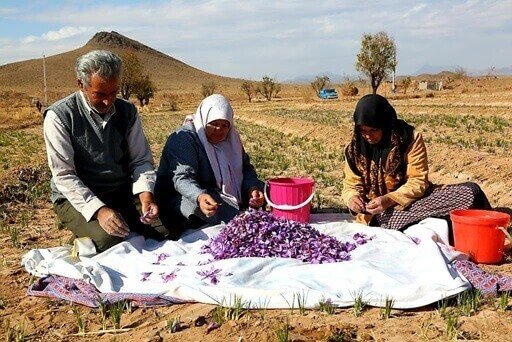

Harvest time transforms our fields into a hive of human collaboration, 8 to 15 family members gathering together in the early morning hours, working quickly before the delicate purple blossoms wilt in the sun. Every stigma, those precious red threads, is picked, separated and dried by human hands.

Let’s begin where saffron truly begins.

Saffron is harvested from the Crocus sativus flower, which blooms just once a year. Each flower produces only three red stigmas, the saffron threads we use in cooking.

To make one kilograms of saffron, you need around 150,000 flowers. And those 150,000 flowers? every single one must be picked by hand.

No machine can identify, grasp, and separate the fragile blossoms without destroying them. Even today in 2025, saffron farming at its core remains ancient, manual, and deeply human.

People often imagine saffron farms as large, highly mechanised fields. The reality, especially in Iran, the world’s largest producer, is very different.

Here is what saffron cultivation looks like for our collective of farmers.

Half a hectare in rural Kerman.

Harvesting is a family affair. Each year, 8 to 15 people gather at dawn during the short harvest window.

From that land, we produce only 2 kilograms of dried saffron a year.

Nothing, absolutely nothing in this process is mechanised. Every gram reflects hours of labour, and every thread carries the fingerprint of the person who handled it.

The Crocus flower must be harvested early in the morning before high noon. once the mid-day sun touches the petals, the flower begins to wilt, and quality degrades. This creates an intense seasonal crunch. All hands on deck. No delays. No shortcuts.

It’s one of the reasons saffron is “labour intensive”, the labour is not spread over weeks. but concentrated into short, pressure-filled window where timing is everything.

When I tell people we only get 2kg per year, they’re shocked. But this is normal for small saffron farms.

What people are really paying for is not just a spice, they’re paying for thousands of hours of human hands and eyes:

Behind every gram of saffron is a village. It’s important that consumers understand this.

One of the biggest misconceptions is “All saffron tastes the same”.

Not even close.

Good saffron has:

Bad saffron produces:

Once, in London, I found a “decently priced” saffron in a shop. At first glance it looked fine, but when I inspected it closely, the threads seemed too uniform, like strings. Real saffron stigmas have a natural, trumpet-like shape.

Another time, I bought saffron that looked good but failed the simplest test:

Place a few threads in slightly warm water. Good saffron releases golden colour slowly. This one released strong orange within 10-30 seconds, typical sign of dyed or low quality saffron.

Knowing what real saffron looks and behaves like is essential if you want to buy wisely.

This is something most consumers never hear about.

In Iran, we’ve seen bulk buyers purchase large quantities of Iranian saffron, and then ship to countries like Spain or Italy, where it’s repackaged and sold at a much higher price under an European label.

This marketing practice means

This is not a criticism of Spanish or Italian saffron, they have excellent saffron producers of their own. But the global saffron market is full of rebranding that hides the true origin.

Understanding this helps consumers make more ethical informed choices.

Here’s an important truth few people realise. A little saffron goes a long way.

A single gram can last a home cook months.

The average person only cooks one or two saffron dishes per month and saffron units of measure are “pinches” and “smidgens”. So if you are preparing a saffron risotto for 4 you only need a pinch of saffron. The important thing is to know how to use saffron in recipes.

When you consider how little is used at a time, saffron is one of the most cost-effective spices, despite its high per gram price.

It’s expensive because it is:

1. Labour intensive

Every flower is picked and separated by hand.

2. Low yield

At best around 150,000 flowers for one kilogram.

3. Seasonal pressured

Harvest must happen within hours.

4. Delicate

One mistake can ruin a batch.

5. Often undervalued at source

Farmers receive far less than the retail price.

6. Frequently misrepresented globally

Iranian saffron gets rebranded, inflating prices elsewhere.

7. Genuinely potent

A pinch or two will transform a dish. That concentration of aroma and colour is rare.

The saffron you use in your kitchen, the few crimson threads you drop into tea or rice represent: